A glimpse into undergraduate research in ecology

by Samantha Gorle

You might know what ecology means, but do you know what an ecologist does?

About Me

I’m Sam, a senior undergraduate student in Biology at McGill University working in the Gonzalez lab, and I’d like to tell you all about my experience as an undergraduate researcher in ecology, and what your future as an ecologist could look like.

I began focusing on ecology as a result of the biology courses I was taking, which exposed me to the wide variety of fields in biology. My main interests revolved around animal biology and diversity, but throughout my studies I found myself enjoying courses about ecology, whether it was looking at ecological dynamics, conservation biology, or studying invasive species. My favourite class as an undergraduate was actually a conservation biology class, taught partially by Professor Andrew Gonzalez. I not only enjoyed the content he taught but his approach to the topics and to his own research. This is what led me to reach out to him to ask about research opportunities, which is how I ended up here!

I hope that writing about my experience in research encourages some undergraduates to explore the possibilities in ecology, and consider the Gonzalez lab!

What I Do

I’m commonly asked what kind of work I actually do as a researcher in ecology, and even what kinds of skills I’ve learned along the way. In this short series I’ll talk about all the cool stuff ecologists do, and give you an insight into my day-to-day work. I’ll also be sure to include some helpful tips for becoming involved in research, so stay tuned for future blog posts!

So, at this point, you might be asking yourself, what is it that I work on? Well, I am currently working with a species of microarthropod, Folsomia candida, is a springtail.

Image taken by Jan van Duinen, acquired from Faddeeva-Vakhrusheva et al. (2017)

These guys are only about 1-2mm long!

Springtails are a great model organism because they have been really well studied, and they are fairly easy to track in their habitats. By tracking them in experimental networks, we can estimate population persistence in a network that reflects the habitat fragmentation that exists in the real world, as seen in the map of Montreal’s protected areas, shown below. Other work has been done in the Gonzalez lab about networks using springtails, as seen in Gilarranz et al., 2017.

This is the map of the Montreal protected area network, from the communauté métropolitaine de Montréal (CMM)

My project focuses on protected area networks and their effectiveness for protecting habitat for mobile species. This has become an important issue for managing protected areas in and around cities. Some cities are looking to protect 17-30% of their remaining natural ecosystems. My project is particularly focused on how effectively Montreal’s habitat network can be protected to maintain healthy populations. I am using Folsomia to study how its populations persist in laboratory models of Montreal’s habitat network – we are making scaled down landscapes to see which habitats and corridors must be protected.

In my day to day lab work, I carry out a huge variety of tasks, which keeps me learning and trying new things.

Since I work with live specimens, part of my routine is looking after them which includes feeding, watering, and maintaining their habitats. For my actual research project, I am building new habitats for the springtails, and then tracking their movements through them. Much of my day to day is in data collection, which for me, is counting abundances in various areas, and sometimes involves taking pictures that can be looked at later.

Much of your time in a kind of ‘wet-lab’ will likely be spent running experiments and collecting data. Something I love about my work is that I get a lot of freedom in designing experiments, and it lets me try a lot of cool, new ideas out, and has led us to some interesting questions. For example, we have been asking about the effects of resources in habitats, and how the availability of food impacts movement decisions, as well as how it affects where a population will establish in a patchy network.

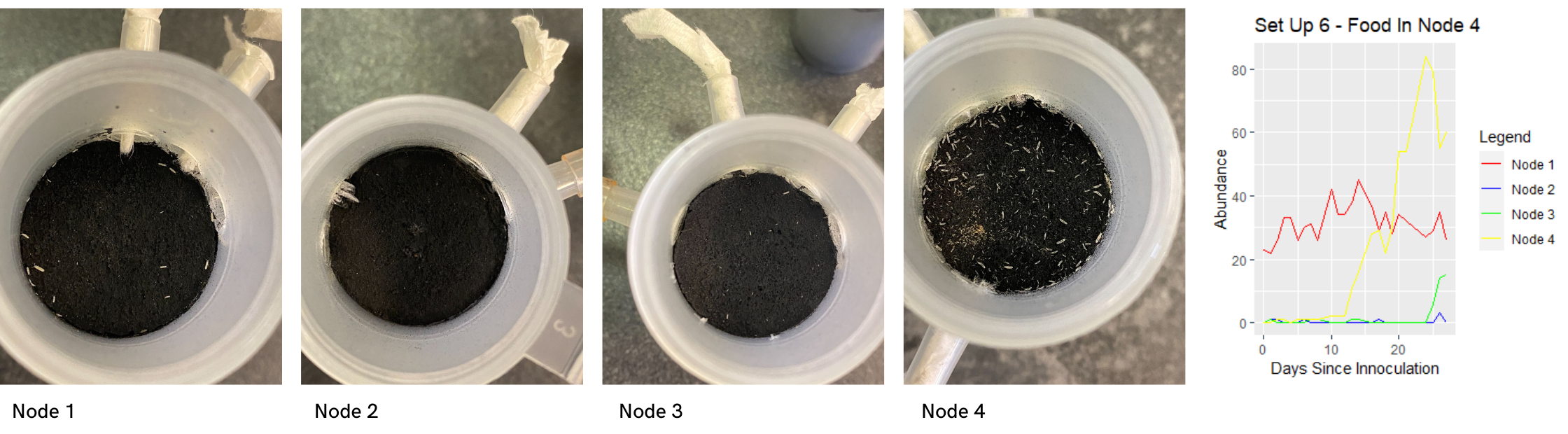

Here’s an example of one of the cool habitat set ups!

This diagram shows the different scales that we are thinking in - there are networks, which can be made up of many nodes, and the nodes themselves, which are only a few centimetres in diameter. Each node contains a plaster & charcoal substrate, with some containing food (yeast), which encourages the springtails to move through the network.

Other tasks include data analysis and interpretation, where I am logging all the data I collect, and then generally creating some kind of visual or statistical representation of what’s happening in the experiments. Here below is a graph that shows the movement between the four connected tubes (nodes) when we start by putting springtails in the first node, and place food in the fourth node. This model shows the abundance (number of springtails) in each node over three weeks.

Here are some updated photos from the set up. From left to right they are nodes 1 through 4.

The analysis step includes graphing or coding to look further at my results, and be able to contextualize them within our research question. This is a key part of any research project, and it is what helps me to communicate experimental progress with my other lab members. I also spend a good chunk of time reading other related papers in my field, which helps me with the interpretation of my results, and keeps me up to date on the literature. This will actually eat up more time than you think, but it’s always fun when you come across a good discovery!

What I’ve Learned

During my time in the lab, I have learned so much from what I’m doing in the lab as well as from my other lab members. I’ve gotten lots of experience with practical, or ‘wet-lab’ skills, such as setting up and maintaining experiments, and collecting data. The practical skills learned in labs may vary, and can even include field work in some cases, but learning practical hands-on skills is very useful moving forward into research. I’m staying in the Gonzalez lab for my Honours project, which is a year long research project completed as a part of my program, and I’m really excited to continue putting the skills I’ve learned to use, and to continue developing myself as a researcher.

As an undergraduate researcher, you can also learn a lot about how to analyze data; this can be with coding by inputting data into certain functions to measure specific metrics about your data. In ecology, we also do some mapping, where we model what is happening spatially, and relate it to the real-life spatial network we are asking questions about. Mathematical models also help you interpret your data, either by creating visual representations or modelling the complexities of the data.

Finally, analyzing and contextualizing your data with what you know about ecology is one of the most important parts of research. Being able to put what I’ve learned into practice has really enhanced my understanding of ecological principles. I’ve done bits and pieces of all of these, and it’s been great to build such a variety of skills that I can continue to use in my scientific career. There are many ways to explore the questions we ask in research and, in my experience at the lab, I’ve felt encouraged to try new things, ask questions, all while being supported by lab members, who have lots of great advice to offer.

Learning from others

Aside from the actual tasks you do and what you learn by doing those, there is so much more to take away from your lab experience. Other lab members are great sources of information to teach you skills, but also to tell you more about their research experience and can provide helpful guidance.

In the Gonzalez lab, we are very lucky to have a lot of members with broad interests, and different skill sets, so we are all learning from each other, which has been such an amazing experience. The lab has members focused more on habitat fragmentation, some on protected area planning, some studying land use changes, and others looking at ecosystem services in mangroves.

Just about any topic related to biodiversity and conservation is being studied by someone, and in so many different ways. Our lab meetings highlight the diversity of work that we all do, and the different approaches we all have, which can be more computational, more experimental, or based in field work.

Your communication skills will also improve from synthesizing papers, sharing ideas with your lab mates, having discussions about your work, and also learning about and engaging with the work other lab members are doing. During lab meetings, it’s always really interesting to hear about what other lab members are working on, and learning about other topics you may not know as much about.

Beyond the lab

Finally, working in the Gonzalez lab has provided me with the opportunity to learn about other paths I could take in my career that I had not previously considered. Of course there are pathways in academia, but also many in industry and in government. With Prof. Gonzalez working across these boundaries, it has been great to see the variety of opportunities there are for researchers, and has expanded my ideas of what it means to go into research. In particular, Prof. Gonzalez co-founded a company called Habitat, where he and other researchers develop nature-based solutions to ecological problems, often in conjunction with municipal governments or non-profits. This is a great example of the kinds of collaborations that can happen between academics, industry, and governments, and is something that makes the Gonzalez lab super exciting.

My experience in the lab so far has been absolutely incredible, and I’m so excited to continue working on my project. Stay tuned for more blog posts in the future - next time I’m sharing some tips for getting involved!